"A name in a hundred

Hinneschied/Hendershot:

a Palatine family of the great

"Auswanderung "

By John E. Ruch

Originally published in

Canadian Genealogist

Volume 4, Number 3. November 1982

Agincourt, Ontario: Generation Press

Canadian Genealogist has ceased publication.

Neither the author or Generation Press

has any extra copies of this issue.

Permission given by author, John E. Ruch, Ontario, Canada,

to reproduce this article.

Annette Ely Schaumann

2807 Bexley Court

Wilmington, DE 19808

Spring 1999

A name in a hundred

Hinneschied/Hendershot:

a Palatine family

of the great “Auswanderung

By John E. Ruch

THE PALATINATE & ONE GERMAN FAMILY

The ancestors of the Hendershot family left Germany in 1709 in the great Palatine Auswanderung (emigration). Descendants of the thousands of Germans who emigrated then are innumerable now. So genealogies of ‘Palatines’ are found frequently in North American publications on ancestry and local history. However, such writings are usually sketchy in two areas: in detailed history of the Palatinate, and in background information on the immigrants. The aim of the present article is to help researchers understand the situation in Germany just prior to the huge exodus. Fortunately, a good deal has recently been discovered about the Palatine origin of the Hendershots which can serve as an example of a particular family and its progress.

At the outset, it must be stressed that in the 18th century the term ‘Palatine’ was very loosely used. Any Germanic refugee or migrant from 1709 on could be called by that name. The first group of them which received much publicity actually were Palatines, and this created the impression that all Germanic travelers were also Palatines. Studies of the immediate origins of the 1709 migrants reveal that they came from well over a dozen different provinces and states—including Switzerland and Alsace. Further, it should be noted that many of those who did emigrate from the Palatinate descended from families which had earlier migrated into that province from elsewhere in Germany. Such was the case of the Hendershots.1

The Palatinate and its history

The history of the Palatinate is eventful, and especially rich in incidents in mediaeval and modern times. Most hunters of Palatine ancestors are, however, particularly interested in the quarter century 1685-1710, the period which saw their forebears come of age, marry and depart for America. But a knowledge of the preceding years of the 17th century helps to give one a better perspective and a fuller picture of life there. Marguerite Dow has already given a good brief outline of German history in the Canadian Genealogist.2. Let us now take a closer view of what was happening to this province and its inhabitants in the 1600s.

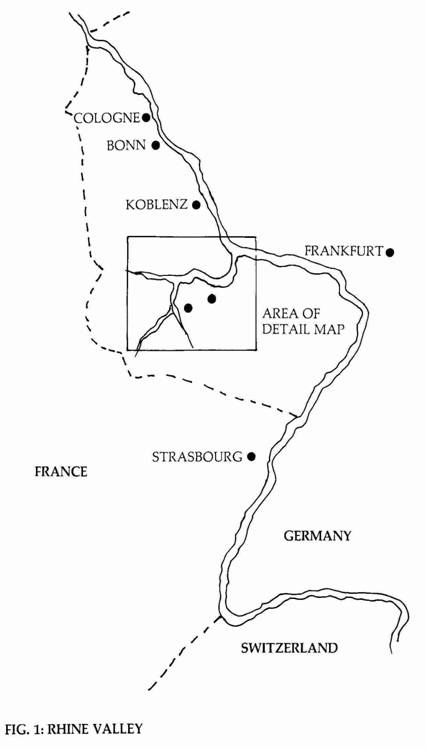

The Palatinate (die Pfalz) was an accumulation of lands under the sovereignty of the Hereditary Count Palatine (der Erbpfalzgraf). It consisted of two main parts: the Lower or Rhenish Palatinate (Rheinpfalz) overlapping both banks of the Rhine River and focused on Speyer for the west bank, on Heidelberg for the east; and secondly the Upper Palatinate (Oberpfalz) north of the Danube near Regensburg. In the early 17th century the Duke of Bavaria seized the latter part, and retained most of it thereafter. So by the early 18th century the ‘Palatinate’ was reduced considerably in size, and nearly all ‘real’ Palatines were emigrants from the Rhine area.3 The problem of a state religion had supposedly been settled by an agreement of 1555 which specified “cujus regno, ejus religio”, i.e., the state must adopt the religion of its sovereign. More than one faith could survive in that state only if the ruler were tolerant. The intolerant were oppressive and caused great hardships for subjects who clung to a non-official faith.

The basic absurdity of this ruling became clear in many states during the next half-century. In the Palatinate there were four successive changes of state religion as four different rulers held sway 1559-1610, alternatively Calvinist (Reformed) and Lutheran (Evangelical). Court cliques surrounding these various rulers were mutually hostile.

Thirty Years War 1613-1648 and its consequences

No part of Germany suffered more in the 17th century than the Palatinate.4 There was seldom a decade without warfare. This began in 1618 when the already explosive rivalries and dynastic squabbles among German states were detonated by an act of Count Palatine Friedrich V. The largely Protestant state of Bohemia elected this Friedrich as their own king. He accepted the office. The Holy Roman Emperor considered this kingdom to be the prerogative of his family. Catholic states rallied behind him, but most Protestant states remained neutral. The Palatine prince's army was defeated almost at once, and the vengeance of the victor was visited upon Friedrich, his country, and his people. His own family, Wittelsbachs of the senior line, was degraded and exiled. The Palatinate was invaded, ravaged, and its people were treated as hostages.

The war did not stop there. State after state joined in a general mêlée. For the next three decades a succession of armies passed through the Palatinate. All were in some degree oppressive, even the ‘friendly’ liberating forces. After the Spaniards came the English, then the Swedes, then the French, and later still, the Germans. Its darkest hour was in 1635-1636 when wandering bands of ruthless, leaderless troops rampaged blindly through the province terrorizing, looting and destroying senselessly. Three years later, in a brief four-month period the Palatinate changed hands three times: von Weimar's army occupied it, was chased out by the Bavarian army, which in turn was expelled when Weimar returned accompanied by French troops. Such incidents represent the unsettled conditions of the time at their worst.

The province experienced a bright period when the war ended. Karl Ludwig, son of the deposed Elector Palatine Friedrich V., returned to rule from 1648 to 1680.5 If any one Palatine living in that troubled century deserves to be remembered, it is he. Even before his return he began to gather foreign support and aid for his ravaged territory. Single-mindedly throughout his life he promoted the restoration of its devastated areas, encouraging immigration, reconstruction and new development. All nationalities and religions were welcomed and tolerated–an unique circumstance in contemporary Germany. His lands made a remarkable recovery in many areas. However, some parts of it were still held by foreign powers, other lords, and some prince-bishops—these were much less well off.

Karl Ludwig tried to preserve peace valiantly, but he was brought into conflict by his strenuous efforts with regard to neighboring powers such as Franconia, Swabia and Worms. In 1665 Mainz and Lorraine united to attack him. He beat Lorraine but the contest with the former was a long-protracted one. In 1676 the Emperor intervened and the problem was submitted to arbitration, a process that lasted forty years. In its central location between France and other German states, the Palatinate was too important strategically to be left alone, even when its ruler declared it neutral. Most armies had extorted ‘protection’ money from Palatine settlements, but when the French invaded in 1672 they had orders from Louis XIV to "burn the Palatinate". It was done under the pretext of punishment for maintaining neutrality, but it was designed to leave the area as a worthless objective for other armies. In quick succession three dozen communities were set to the torch, including the cathedral and city of Speyer. Again in 1678 the whole Rhine valley along both sides from Trier on the Mosel, south to the Ortenau in Baden was treated to the same sort of destruction.

At this point there are two important observations to be made for the genealogist. First, 1618 to 1648 saw many foreign and non-Palatine German armies quartered in the Palatinate for varying lengths of time. On retreating these multitudes left many of their members behind, men who had deserted or simply decided to settle here. They helped to fill the gap caused by tens of thousands of missing local people—natives who had been killed, died of plague, or simply fled to more peaceful states. Estimates of this loss range from 98% to 30%.6 The truth seems to lie about half-way between these two—around 60%. It seems tragic that a number of Palatine Protestants from the Upper Palatinate had already sought refuge in the Rhenish province from a zealous Bavarian Catholic regime in 1623.

Secondly, from 1648 on during the reconstruction period, Karl Ludwig persuaded many groups to immigrate from nearby states. These included Walloons from the northwest, exiled English Puritans who had settled in Holland, some Dutch Reformists, Mennonites from Switzerland, and Huguenots from France. As implied above, the Palatinate was in a central position which made it a ‘cross-roads’ or ‘buffer zone’ between more powerful states. The Count Palatine revived an ancient imperial law which gave him the right to claim all homeless and illegitimate persons as Palatine subjects. This was the Wildfangrecht which now permitted him to seize such people on the ill-defined border areas of his state. Thus, using every means in his power to repopulate the land, did Karl Ludwig bring more ‘foreign’ settlers in.

Late 17th century—the ruling dynasty

The Wittelsbach family ruled here as Counts Palatine from 1214 on, although their junior branch had already been Dukes of Bavaria since 1180. The senior branch later acquired also the influential rank of Imperial Elector (Kurfürst) and besides enjoyed vice-regal status in the Holy Roman Empire, in precedence being second only to the emperor himself. As descendant lines multiplied, problems of inheritance and succession became ever more complicated. Counts Palatine 1559 to 1685 were of the "Simmern" line, which tended to be of the Reformed religion. Upon extinction of this branch, the succession should have gone, by an old agreement, to one of the "Zweibrucken" lines. The latter disputed among themselves, and the problem was resolved by the Imperial council which chose the Catholic branch of "Neuburg-Sulzbach" by a majority decision. This had unhappy consequences for the Palatinate. The new rulers were already long in possession of the Catholic duchies of Jülich and Berg, which they much preferred to the less fortunate Pfalz. They remained in the north, and governed the latter by regents—four in ten years scarcely made for continuity of administration.

There did, however, begin a strong Catholic influence with the succession of Philip Wilhelm (1685-1690). His son Johann Wilhelm (1690-1716) left most of the direction of affairs in the hands of his Jesuit advisers. Militant religious orders were encouraged to immigrate. French invaders supported the zealots and gave them the military force they needed to oppose the large Protestant majority of the Palatinate. The effect was slowly to squeeze the Protestants out of their religious buildings and properties, out of all official posts, and out of their other civil rights. It is ironic that in the early 1690s, the Palatine Catholic leaders took the side of the French enemy to enforce religious conversion in their province, and that the strongest opposition to such fanatics came from the French Intendant (governor of the occupied territory) La Groupillière.

After eight years of occupation from 1688, the Treaty of Ryswick and other enactments brought into effect new forms of oppression in devious ways. An example of this was the regulation which forced Reformed Protestants to share their churches and church incomes with Lutherans and with Catholics where the latter had not enough parishioners to support a church of their own. This forced religions together most unfairly—but it was not reciprocal. Catholics were under no obligation to share anything with Protestants in places where circumstances were reversed.

So ominous did the repressive measure appear that Palatine Protestants sent representatives to plead with foreign princes for help. In 1705 Prussia issued an ultimatum: she threatened to confiscate Catholic property in her own territories unless the situation changed. Strong pressure from such foreign powers, as well as concerned Catholics, forced the Palatine zealots to compromise, but ingenious jesuitical bargainers still managed to obtain terms which could be later manipulated in favor of Catholicism. A full appreciation of the innumerable repressive devices which they used then and throughout the 18th century can be got only by reading a detailed history of the period.7

History's raw material: a Palatine family

Hinneschied of Naumburger Hof

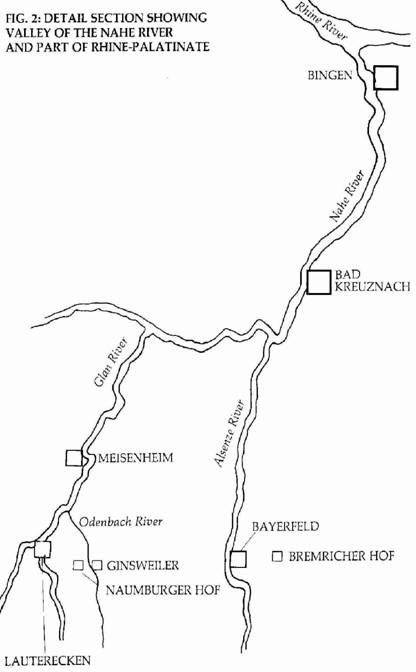

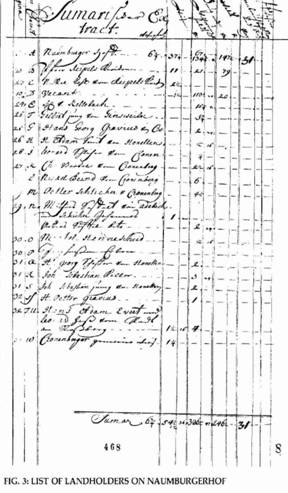

We have now reached the period in history which the Palatine emigrants of 1709 experienced personally. Our attention can be more narrowly focused on the locality in which the Hinneschieds lived, their farm and its own history. We know of two related families of this surname which settled in the Nahe River area of the western Rhenish Palatinate south-southwest of Bingen. Both leased large, neglected farms—one the Naumburger Hof in 1673, the other the Bremricher Hof about 1690. The emigrant of 1709, Michael Henneschiedt, left the former which continued to be held by his family for three more generations. (Some of his relatives from the latter Hof may have also emigrated later.) There are extensive dossiers of both farms in the Landesarchiv, Speyer, which give an illuminating view of the families and their progress. Here we shall mainly confine our remarks to the emigrant's family Hof.8

The Naumburger Hof farm existed long before the arrival of the Hinneschied family. A study of its past reveals much about the life of common farmers, and illustrates in stark reality how they fared through the tempests of nature and the blasts of war. We can see the various events of political, religious, social and economic history directly affecting the Palatine folk (die Pfälzer).

A Hof was roughly equivalent to an English manor owned by an absentee landlord. Essentially a Hof was an estate, sometimes one of many, which belonged to a nobleman who rented it to common farmers. There were a great many of these in Germany, and many places and people took their names from them, hence Nordhoff and Hofmann. The head man of the farm, whether he was the lord's steward or a peasant tenant, was called a Hofmann and his family members were known as the Hofleute (lit. court folk).9 Naumburger Hof (lit. New-castle Court) was the home farm of a small castle which when rebuilt was dubbed the New Castle. It, in turn, was destroyed five centuries previously, and its stones were used by local people for building their own houses and barns.

Landlords of this estate by the mid-13th century, were the Counts von Veldenz. This family failed several times in the male line, and title and properties then passed through the female lines into other families. From the mid-15th century on this meant a branch of the Palatine Wittelsbachs, the lords of Zweibrücken. By the 17th century the Zweibrückens had three divisions: the dukes of Zweibrücken, the counts of Veldenz, and the counts of Neuburg-Sulzbach. The presence of the Swedish army in the Palatinate during the Thirty Years War had more far-reaching effects than is sometimes realized. One of the Zweibrückens, through his military associations with them, married a Swedish princess. By the quirks of fate, as one family after another failed of male heirs, this particular division became in turn kings of Sweden, and counts of Veldenz, as well as dukes of Zweibrücken. This remarkable combination of lordships existed for one generation only in the very period with which we are principally concerned. Thus, in 1695-1716, when the farmers of Naumburger Hof addressed their landlord, the salutation was to the King of Sweden, although their petition traveled no farther than the local county seat at Meisenheim.

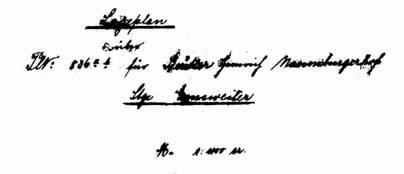

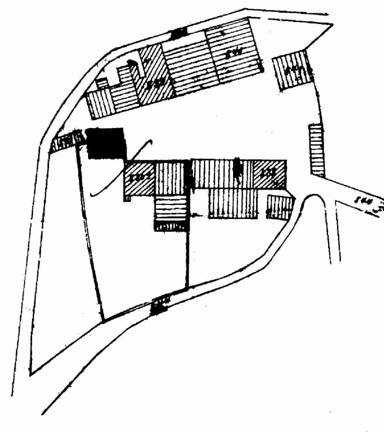

The Veldenz property overlapped both sides of the Glan River, a tributary of the Nahe. It was approximately 15 miles broad by eight miles in depth, but of a very irregular form. In outline it vaguely resembled the head of a roaring lion turned to the left and tilted downward, the eye being formed by Meisenheim. (Coincidentally, the count's coat of arms was a blue lion rampant on a silver shield.) Naumburger Hof is about five miles south of the county seat on the Odenbach stream. Its buildings are perched high up on the closely-grouped hills of its 450-acre lands. There are several descriptions of the Hof in the records preserved at Speyer, which begin in 1540. A detailed account from forty-five years later gives very clear references to the bounds and boundary markers along the entire circumference of the farm. Not until 1706, however, was an accurately-measured survey made. This map, together with a descriptive notebook, shows every field and pond, names the tenants holding each plot, and tells something about each field, its use and soil. 10

In less

troubled areas of Germany it was common for one family

of Hofleute to be rooted in possession of Hof lands

for centuries. Although no one family held Naumburger Hof throughout its

centuries of existence, we can gather a very clear impression of the

vicissitudes of a Palatine farmer's life. The conditions of the 16th century

contrasted sharply with the following era of wars. From the 1585 inventory we

get the impression of fruitfulness and prosperity which continued until about 1620.

Fertile fields under cultivation barns filled with harvests, woods and ponds

stocked with game and fish, wine-making in progress, and all buildings sound

and in good repair: this was Naumburger Hof.11 Even in

a bad year the tenant could break even. His rent could be raised from

13 bushels each to 15 bushels each of oats and rye per year without hardship to the tenant. There was running water piped down from a spring higher up the hill. Leases were for 15 or 21 years.

This golden period ended with the coming of the Thirty Years War. Disaster followed closely upon disaster. In 1622 Spanish troops plundered the Hof stole the cattle, damaged the buildings, and thus drove out the Fischer family. Abandoned for four years, the farm was subsequently taken up by a squatter, Saltpetersieder, who later took formal possession. In 1632 Swedish cavalry completely pillaged the farm. From a contemporary statement we learn of everything they took, right down to the number of eggs, cheeses and pounds of butter.12 Grief-stricken, the tenant succumbed to the plague. His son carried on, but in 1642 soldiers robbed him of his oat harvest. He relinquished the farm to one Schuhmacher in 1644. Three years later troops looted all moveables and destroyed his crops. In 1648 the war ended but the crops failed. From then on, several partnerships of farmers worked the field, which were now infertile and poor. This condition persisted for decades thereafter. The natural cycle of agriculture had been broken, and the trend had become that of a vicious downward vortex. Diminishing input led to diminishing returns and so on, the resources continually declining: scarcity of workers, animal stock, and fertilizer, infertility of soil, poor harvests, shortage of food, fodder, seed.

Disastrous as the war had been, and as harsh as its consequences were in general, some conditions improved. The landowners, suffering from a very sharply reduced income, were burdened with problems of repopulation, estate management and reconstruction. Neglected or derelict farms with ruined buildings had to be made livable and productive. Although the labor fell onto the shoulders of the farmers, the very scarcity of tenants meant that owners had to offer easy terms and low rents to attract them. Long-term, and permanent leases were offered instead of the old shorter contracts. This gave peasants greater security, and the motivation to invest in improvements which they and their heirs could enjoy. Feudal obligations were relaxed or ignored. The tenants became more independent, challenging the lord’s rights and exploiting his weakness whenever that could be done with impunity. Many of the peasants had survived the invasions by their wits, and were canny farmers, not mere passive serfs.13

The leases of Naumburger Hof and Bremricher Hof were converted to permanent hereditary contracts (Erbpacht) renewable on the death of either lessor or lessee. The former Hof was in somewhat better condition than the other, and soon found a lessee, Wilhelm Hinneschied. Bremricher Hof had not been inhabited within living memory, and (it was said) oak trees had grown up in the fields with trunks "as thick as hogshead barrels". It lay waste another twelve years. Eventually Wilhelm's relative, Johann Peter Hinneschied, settled here with his family. At Naumburger Hof Wilhelm and his brother-in-law Mathias Krebs, a trained carpenter, rebuilt house, stables and barns. Wilhelm died in 1688, but his family continued in possession until 1776.

We find more and more

records of the Palatine farmers as the generation of the emigrants approaches.

However, they must be evaluated with caution for these are documents from their

landlord's offices—accounts of stewards, estate managers and rent collectors.

There are many new and renewed leases, plus numerous petitions from the tenants

for reassessment, remission or reduction of rents. No doubt many of the

hardships claimed by the farmers

were exaggerated, but when the landlord accepted all the Naumburger Hof cattle in 1689 to make up for arrears in rent, we can only conclude that the Hofmann was in dire straits indeed.

In general, the experience of Wilhelm's young family toward the end of the 17th century was likely typical for Palatines in the Rheinpfalz. Here the population was rapidly replenishing itself, perhaps too quickly for its resources in view of the frequent demands of the military which constantly drained them. Troops raided the Hof in 1675, 1679, and 1688. Palatine soldiers were billeted there in 1702-03. Crops were consumed by a plague of snails in 1679 and 1694. Harvests were destroyed by hailstorms in 1681-82, and 1696. Yet we hear of no mass starvation in spite of these conditions.

The really critical period came with the black years of 1707-1709. A foreign invasion was followed by crop failure, and then by the coldest winter in living memory, and finally famine. At this very time, colonizing agents passed through the Rhine Valley singing the praises of pioneering in Pennsylvania, and of the generous protection of England's Queen Anne. Naturally, the Palatines and others were quick to respond to this appealing alternative. One is surprised to find that so many remained behind at home in what looked like permanent depression.

The winter of 1708-09 must have seen a good deal of discussion of emigration plans. By spring many attempts had already been made to dispose of leased and other properties as quietly as possible before embarking on the great adventure.

At Naumburger Hof the succession to the Hof lease was the subject of a long-standing dispute. Wilhelm had died in 1688 leaving his wife in charge with the assistance of a son-in-law. As Wilhelm's sons reached legal age they expected to inherit the tenancy, but a contest developed with their sister's husband. Several appeals were made by their mother to the landlord, and one of these significantly was dated in early 1709.14 She petitioned that her fourth and youngest son be confirmed in possession. This was in accord with a common principle of Jungenrecht (junior right) in contrast to primogeniture, the right of the eldest to inherit the whole. Since in large families elder sons tended to marry and move away, while the youngest was the last to remain on the farm, he was allowed to inherit on the condition that he compensated his brothers and sisters for their equal shares in the inheritance. We do not know the exact decision of the lord, but we are not surprised that the eldest son emigrated shortly afterwards.

Michael (1674-1749) emigrated and was probably not sorry to leave behind him the continuing family disputes. His parents Wilhelm Hinneschied and Anna Maria geboren (born) Balter had had eight children. The great family misfortune was the early death of Wilhelm in the very year of the French invasion. He was a lapsed Catholic, his wife a Lutheran, who brought up her children in her faith. With the support of the French and a degree of reason, Franciscan monks claimed half of the family for conversion to Catholicism, taking the four younger children away from their mother. After a period of indoctrination they were returned to the farm. At least three married within that faith and brought their spouses home. The consequences were very troublesome. First, the Hof was soon overcrowded with the adult children and their offspring. Secondly, religious differences became a constant source of bickering and quarrels.15

Author’s Note: The Hinneschied house and barn are no. 838 and

the unnumbered building on the same lot (no. 837) on the map

HINNESCHIED OF NAUMBURGER HOF

Wilhelm Hinneschied (Hennenschiedt, Hünershut, Hinderschied, etc.) b 1640? Duchy of Berg, d 1688 Naumburger Hof, Palatinate, Hofmann (chief tenant) of Naumburger Hof 1673-1688, m 1663? Anna Maria Balter, sister of Peter Balter, a carpenter of Medard; she b 1640?, d 1724 after a 2nd marriage of seven years; Hoffrau (chief tenant 1680-1720).

Children

1. Anna Maria, b 1670?

m Theobald Hart (Haack) 1689, Feilbingert (R.C.)

2. Anna Magdalena, b 1672?

m Daniel Lamine (Lamereck, Lammenech) 1690, N. Hof (Prot.)

3. Johann Michael (Henneschiedt, Hindtershit, Hinterschied, etc.)

b 1674, d 1749 Hunterdon Co., N.J.

m Anna Catharine (Schneider?), 1698? (Prot.)

emigrated 1709, arrived New York 1710, Hunterdon Co. 1712-13

4. Johann Peter, b 1678?

m Maria Cohnss [sic], 1698? (Prot.?)

5. Maria Catharina, b 1680, bapt. Heimkirchen

m Adolph Schuhmacher, 1700? (R.C.)

6. Johann Christoph (Hünescheidt, etc.) b 1682, N. Hof

m Maria Margaretha (Prot.?)

7. Johann Anton, b 1684, N. Hof

m Anna Elisabetha Weigand, 1708, Meisenheim (Prot.)

8. Maria Elisabetha, b 1686, N. Hof

m Meinrad Köhlmeier, 1704? (R.C.)

The later progress of the Hof exemplifies one aspect of the progress of Palatine history. Gradually the lot of the farmers improved as wars and invasions became less frequent. They could reap the benefits of their own, or their father's labor. Anna Maria was succeeded by her second son Johann Christoph in 1720. The landlord was able to raise his rent because productivity had in-creased. When Joh. Christoph turned over the Hof to his children Joh. Sebastian and Joh. Jacob in 1747, the value of the hereditary lease was estimated at 3,000 gulden—a far cry from 1673 when it had gone begging, the fields overgrown, the buildings a heap of blackened stones.16

Curiously, bad luck dogged the Hof families both here and at Bremricher. In each of them matters followed a similar course: the surname Hinneschied disappeared from leases in the later 18th century, although their descendants by other surnames remained as tenants and workers. Their traditional farming methods were losing out to the more efficient and organized ways of Swiss Mennonites who moved into the area gradually replacing them. The last Hofman, Joh. Jacob's son Georg Wilhelm, was bankrupted by the failure of a stock-breeding project. In 1776, one hundred and three years after his great-grandfather Wilhelm had moved in, this broken man left Naumburger Hof.

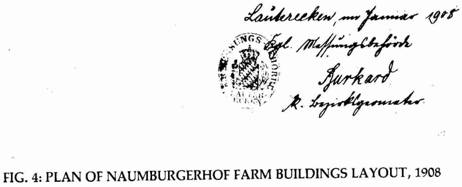

The vicissitudes of the Hof

economy are reflected in the existing buildings. The old court yard lies

halfway up the hill from the village of Ginsweiler. It is

a long, narrow area enclosed on three sides by alternate houses and barns, of

stone or half-timber construction (Fachwerk). The small house at the near

corner is the oldest of the group and was inhabited by the Hinneschieds. It has

a stucco façade which hides a stone-walled ground floor,

and a half-timber upper story. The doorway keystone is inscribed 1747 indicating the time at which the prosperous Hofmann either rebuilt or renovated the dilapidated original home. Most of the remaining buildings were constructed much later by new tenants–Swiss style houses and huge barns. These clearly indicated changed circumstances, increased productivity and profitability. But today they are chiefly in bad repair, some derelict. Machinery has replaced many of the farm workers, and fewer farmers need fewer houses. The wife of the present resident, Herr Karl Greilach who guided us around the Hof, was born Beutler. She is descended from one of the Swiss immigrants, and is the last resident who was actually born on the Hof to a family of the old Hofleute.

THE EMIGRANT HENNENSCHIEDT FAMILY

Traditions and facts

The emigrant family brought certain tales to America which have confused their descendants for generations. In the 1890s, some wishful thinking was added to the mixture, and a completely erroneous ‘tradition’ was produced. This oft-repeated fabrication has been embroidered since then in various ways. Essentially, the family was supposed to have descended from minor nobility which was exiled on grounds of religion and lost its estates.17 The seed of this story was a misinterpretation of words like Hof and Hofmann, and misunderstanding the hereditary leasing system. Certainly, news of the Hof settlement of 1747 upon their cousins who remained at home must have given rise to envy, and in later years to legends of the family having been dispossessed of a rich property in the old country. The documents discovered since 1974, and mentioned above, make it clear that Wilhelm, his wife and children, were unlettered country folk. The closest they actually came to court circles was through the third son of Michael's Hofmann brother, Joh. Christoph. This Joh. Ludwig was fortunate enough to be trained as a cooper, and marrying a brewer's daughter, became a citizen and court cooper (“Bürger” and “Hofküfer”) to the ducal household at Meisenheim.18

Confusion arose not only from the foregoing misinterpretations, but also from a mingling of diverse and irreconcilable traditions. Lack of reliable documentation led numerous American families to claim descent from Michael as the earliest known immigrant of their name. They grafted their own oral history onto Michael's branch. Such genealogies are usually betrayed by a large time-gap between the details of Michael's immediate family and those of their own in the late 19th century, different naming patterns of children, and different places of origin. These families are usually unaware that many other Germans of their surname immigrated in the 18th to 20th centuries. Some of these later comers gave their origins as Baden, Bavaria or Prussia. Yet they seem to have come from not far apart in the general area of the Rhine Palatinate, which in the 19th century was divided among those three powers.

A name in a hundred

Linguistic experts tend to agree that the surname Hinneschied/Hendershot is literally based on Hund, the ancient word for a ‘hundred, or the chief of a hundred’.19 The first forms in which Wilhelm's name occur are dated after his emigration from Berg to the Palatinate. The first vowel caused writers so much difficulty to render that it must have been a diphthong, either ä, ö, or ü. Thus, it must have derived from either Hönsdeid or Hänscheid, hamlets close together near Blankenberg, in Berg. Freely translated these mean the ‘township meeting place,’ a community clearing (“Scheid”) in the primeval forest which covered much of Germany during the early Middle Ages. So Hinnenschied/Hendershot would mean a person from the one particular place of this name. The first syllable of the place-name evolved from Hund, a word used both in Old German and Old English. A ‘hundred’ was in both countries a small local jurisdiction of roughly the area of a Canadian township. Used of a person Hund meant the chief man of the area. In English a ‘hundreder’ was either an inhabitant or the chief of the hundred.

In America about 1750 the New Jersey families began using an anglicized form Hendershot more or less regularly. But in Pennsylvania in the next few decades the German form evolved into Hinershitz. The 19th century immigrants who usually settled farther west, in German-speaking communities, continued to use German forms of the surname, and not being in contact with the earlier families, were unaware that the Hendershots were their relatives.20 One very unusual change was made in the 1920s by a veteran of the German army. When he immigrated, Heinrich ‘Heinz’ Hinneschiedt changed his name to Hennessy, which he said sounded like his surname—but could be spelled more easily by Americans.21

The Hendershot family in North America22

The remainder of this study is devoted to the first branch of the family to emigrate to America After dealing with Michael and his children, the line of the Loyalist branch will be followed to Canada after the American Revolution. Michael's other descendants are too numerous and widespread to cover in so short a space.

Michael Henneschied and his family left Germany with a group of friends, neighbors and relatives from the area of Meisenheim in early 1709. They joined the mass migration to America, reaching London in late July, but not arriving in New York until the following June. A year later Michael went up the Hudson to work on the government's naval stores project, possibly as a foreman.22 When this scheme failed in late 1712 his group of Palatines moved south to settle in the Raritan Valley of New Jersey. Michael and his wife Anna Catharina (born Schneider?) had three children already, and four more were born in their new home. Of the seven, the four boys were Casper, Peter, Michael Jr., and John; their sisters were Maria Rosina Catharina (sometimes called Sophia), Elizabetha and Eva.

MICHAEL HENNESCHIEDT OF HUNTERDON COUNTY, N.J.

Michael Henneschiedt (Hünneschied, Hunershut, Hindtershit, Hinterschid, etc.) b Palatinate 1674, d Rockaway, N.J., 1749 m 1698?, Anna Catharina (Schneider?), b 1680, Germany, d 1757, emigrated July 1709 Rotterdam to London, arrived New York June 1710, subsisted there until September 1712, settled shortly thereafter in New Jersey.

Children

1. Casper b 1699 Palatinate, d 1768 or later in N.J., m Catharina (Shipman?)

2. Johann Peter Hünescheidt, etc., b 1702 Hohenöllen, m (Ann Melick?)

3. Maria Rosina Catharina Hinnescheit, etc., b 1704 Hohenöllen, m (Samuel Swickhammer?)

4. Johann Heinrich Hindescheit, etc., b 1706 Palatinate, d probably as an infant

5. Michael, b (1713 Raritan Vallye, N.J.?), m Elizabeth Schermerhorn

6. Elizabetha Hinshutt, etc., b 1716 Raritan Valley, N.J.

7. Eva Hunschutt, etc., b 1717 Raritan Valley, N.J., m (William Pippenger?)

8. Johannes Hunneschutt, etc., b 1720 Raritan Valley, N.J., d 1798 Greenwich Co., N.J., m 1st Ann Schooley, c1744; 2nd Catherine Bodine c1755. The tradition that he also m c1750 Johanna von der Lindt probably should refer to the John George Hindershit who immigrated in 1749.

Sinners, preachers and others

Much of our knowledge about this group of families comes from church records. Michael was very closely involved with the local Lutheran congregations in Hunterdon County, and for many years was "der älteste in Rochaway”, leading elder in the Rockaway Congregation, i.e. around Potterstown. He was not a placid or docile creature, but had a fiery temper like his father, Wilhelm, who had once threatened to burn down his Hof rather than submit to the tax collector's unreasonable demands. The three principal disputes of his tenure involved the pastors Falckner, Wolff and Weygand. The first came to a head because he dismissed the aged and feeble Daniel Falckner whom he found going home from Sunday service inebriated and singing in 1731. This caused a furore in the church. Secondly, both he and his son Casper were among church representatives sued by the notorious Johann August Wolff in suits lasting from 1737-1747. The expenses were heavy because this difficult parson, who married a local farm girl, actually won in an arbitration the back-payment of his salary, although he had consistently neglected his pastoral duties. In the late 1740s Michael belonged to the faction which opposed calling Johann Albert Weygand to their church. The latter in his Diary gave Michael a hypocritical character when describing the dying old man.

This man had stained his soul with many sins of unrighteousness as I learned from people who had known him from his youth up . . . but he made himself out so pious, that I had almost never met a man so pious as he appeared to be.

Even if his description is true, we can still detect a certain amount of ‘one-upmanship’ or pious gloating in Weygand's account of an old reprobate brought to repentance. Weygand persisted in visiting and preaching and performed a miracle. At the end of two more weeks, after singing a hymn with the pastor, Michael died—apparently full of grace. The greatest of the immigrant Lutheran ministers in the 18th century, Henry Melchior Muhlenberg, often rode a circuit through from Pennsylvania. He, too, had chats with Michael in his last and lengthy illness, and made veiled references to him in his Journal. Perhaps this saintly man had more effect upon Michael than the local preacher.23

The church was indeed the centre of pioneer life in this area of New Jersey, although it was difficult to find good pastors. There were four congregations not far apart here, and three of them united to build Zion Lutheran Church in 1749—shortly after Michael died. He had lived near Whitehouse, Reading(ton) Township. The new church was built about a mile north of there in Tewksbury Township at a place where the village of New Germantown quickly grew.

Michael's family continued to take an active role in church affairs in the next generation. Casper, of Amwell, served many years as trustee and elder. Michael, the younger, built a two-story stone house directly opposite the new church. Although there have been changes made to both buildings, they survive today. The centre line of the old main church door is on the same centre line as Michael's front door.24 Since the house was taller than the cabins around it, it was long known as Hohenhaus, the high house. There is evidence that young Michael was a tavern keeper. John, on the other hand, was a farmer about ten miles farther north, in German Valley. Mühlenberg used his barn as a church when he preached in that neighborhood.25

From Cushetunc to Ozenbrig: old names, old places

Mention of the locations of the Hendershots in New Jersey can be mystifying because boundaries as well as place names have changed. For example, in 1917, in a fit of patriotism, German Valley and New Germantown were disguised as Long Valley and Oldwick, and still retain these names. However, geographic bounds are quite another matter. When the land was new and little explored, vast tracts were laid out and named often by men with only vague ideas of the character of the countryside. As settlers multiplied many times over, ever newer and smaller political divisions had to be created. Thus Hunterdon County (established 1714) was eventually sub-divided into six counties. Of the original four "towns" in it, only one remains in the shrunken Hunterdon. This is Amwell Township, but in itself had been divided into fifteen parts already in the late 19th century. In the period of this article, about 1750, it had had only five townships; in clockwise order from the north, Lebanon, Reading(ton), Amwell, Kingwood and Bethlehem. The boundaries radiated from a small area near Cushetunc (Pickle's) Mountain. The early Hendershot families were distributed fairly close around this same centre.

A future genealogist who wants to understand this family's history clearly will have to study local history with great care. There are numerous tantalizing references to the family which will only make sense to someone who knows the political, economic, legal and social background. In court records both of county court and the supreme court there are indications of many legal actions in which they were involved. The proprietors of West Jersey lands tried to evict them (Michael, Casper and ‘Henne’) and their neighbors from land which the Society had leased to them.26 Between 1737 and 1767 the following Hendershots were involved in suits: Michael Sr. and Jr., Casper, Christopher, Jacob, Jeremiah and Peter.27 Some of these actions were over unpaid debts.

More incidental light is thrown on their everyday life by the records of shopkeepers, e.g. Janeway, and Nitzer. The family from around Oldwick were customers in 1736-47 of Jacob Janeway who had a general store twenty miles southeast near Bound Brook, an important cross-roads by the Queen's Bridge—the earliest village in Somerset County. Jacob, Jeremiah and Peter were from Long Valley and had accounts at Nitzer's store in that area in the 1760s. Cash purchases were not recorded, but fortunately credit accounts were, and bills were settled at intervals in kind with bushels of wheat, buckwheat or flax seed, or even occasionally a whole hog. These purchased supplies of all sorts. For the house and food-preserving were quantities of rum, molasses, sugar and spice. For use in the fields and hunting were straw hats, hobnails, powder and shot. But a substantial number of items were for making clothing: ribbons, thread and various kinds of yardgoods for linings and light clothes—shaloons, romals, kerseys and ozenbrigs (Osnaburgs).28

The third generation of Michael's family, i.e. his grandchildren, was numerous—some estimate there were three dozen of them. Because certain names were popular (Michael, Peter, John and Casper) and records are scarce, there is much confusion concerning which person was which. Casper (1699-1768 or later) was a farmer in Amwell Township near modern Ringoes, but from early 1735 was also Hunterdon County commissioner of highways. His wife Catharina (born Shipman?) gave him several children of whom one is known to have been Peter born 7 January 1733 (N.S.). In the church register the surname is mistakenly entered as "Henrich

Schutse"29 There seems little doubt that he was the Peter who became a Loyalist soldier, and that an Isaac Hendershot who did likewise was his brother. Yet another brother was probably Christian or Christopher, who came to Canada late.

New Jersey and the Revolution

The Revolution divided a great many families into rebel and loyalist factions. It was the deciding element which greatly increased the dispersal of branches of established families from the localities of their birth. The Dutch and German groups had a tendency to remain loyal to the British Crown which had given them a new land, assistance, religious tolerance and protection in a hostile environment.

Of all the American Colonies, New Jersey contributed the greatest number of soldiers to a single Loyalist regiment. The colony itself has been called the arena of the Revolution for it was the scene of much military activity and fighting. While the British army occupied Philadelphia 1777-78, New Jersey was an overwhelmingly loyal area. However, General Howe's incredible bungling of the whole campaign allowed New Jersey and Pennsylvania to be converted into rebel camps.

Beginning in July 1776, Cortlandt Skinner raised a loyal regiment called the New Jersey Volunteers. Officers such as Isaac Skinner, and several Bartons recruited large numbers of local men. After the war the veterans spoke of their units often as, "Skinner's Greens" or "Barton's Corps," etc., rather than as the Volunteers.30 Muster rolls of both the loyal and rebel forces show how many of the families were split. Several Hendershots were on the rebel side eventually. In the Volunteers' ranks were Peter, Isaac and Peter's son-in-law Michael Henn. The latter appears to have served without incident, but Peter was captured by rebels in 1778. Their principal camp was on Statten Island, just off the Jersey coast, and Peter had slipped through the enemy lines to recruit when apprehended and jailed. Isaac was sent on the expedition to Carolina, became ill, and disappeared from the rolls without explanation.

THE LOYALIST LINES

The Hendershots who had remained loyal to the British government joined the exodus of persecuted refugees to Canada. The families of Peter and his son-in-law Michael Henn reached the Niagara district about 1785-86. There were many such Germanic families settling in the area, which continued to attract Mennonites from Pennsylvania, and direct German and Alsatian immigrants in the 19th century.31 In 1805, Christopher Hendershot brought his family in from New Jersey to the Hamilton-Toronto area. The "loyalty" of some early members of his two of his sons deserved inclusion in the roll of honor for the 1812 War.

The Principal Peter

Since the 17th century Peter has been a favoured name in the Hendershot family. This constitutes one of the principal problems for a genealogist in the U.S. and Canada. We think that the following details all relate to one, the Loyalist Peter, but identification is still uncertain in some cases. Peter married Priscilla, daughter of William Philipps, in the mid or late 1750s. She was received into the Lutheran church by Pastor Mühlenberg in 1758. They had two children baptized when they were living in Lebanon Township; Johannes in 1770 and Priscilla in 1773.32 However Peter the Loyalist must have had at least two, possibly three, more children. Sarah born about 1760, Peter born 1775-76, and perhaps a William. The younger Peter claimed to have been born in "York State". Sarah was many years older than he was, and was beginning to have her own children in the late 1770s or early 1780s.

In Canada no land was ever claimed for Peter Hendershot Sr. Thus his "U.E. Right" went unused until Peter Jr. petitioned for a land grant in 1795. Although he had been a child at the time of the Revolution, Peter the younger was accorded U.E. status. This was fortunate for his family, since he had eleven children of his own, each one of whom consequently was entitled to a land grant as a son or daughter of an U.E. Loyalist. About the time he petitioned, Peter had married Anna Jane Crow (1776-1842), daughter of Johannes Groh, a Dunker—better known as "John Crow"; the latter did not qualify as a "U.E. Loyalist". Nevertheless, he did obtain a grant in Pelham Township where Peter and his children were resident. The Crows and Hendershots were much intermarried with other local families such as Comfort, Disher, Johnson, Moore, and Moote. Another local family was related through the marriage of William Hendershot to Christine Bowman, daughter of Abraham. William is a mystery. He claimed no land, although he would have been of the same generation as Peter Sr.'s children. After at least five years of marriage he went to the U.S. following the 1812-1814 War and never returned. Christine remarried between 1816 and 1828, her second husband being Moses March.33

The early generations of immigrant families give some striking examples of their growth in prosperity once the pioneering stage was over. Somewhat similar patterns are observable in the Palatinate c1730, in New Jersey c1750, and in Niagara after 1800. In each case, one or two Hendershot families had already immigrated to territory that had to be reclaimed from ruin or pioneered from scratch. The parents were either illiterate or too busy and poor to provide book-learning for their first children, but the youngest in large families usually benefitted from the labours of their elders being as it were borne upon their shoulders to reach a higher rung on the ladder of advancement from youth on. This is particularly noticeable in the family of Peter Jr. Some of the older sons and all of the daughters could not write their names. Younger sons signed with a little effort, but the youngest, William, wrote easily.

Peter's Legacy34a

Peter Hendershot (1775?-1819) and his wife Anna Crow (1776-1842) had eleven children reach maturity.

Elizabeth (c1797-188l) m David Moore.

Mary (c1800-l871) m Henry Johnson of Pelham, 1818?

Abraham (1801-1861) m Hannah Thomas.

John (c1802-after 1845).

Jacob (1803-1855) m Jemima Stewart.

David (c1805–between 1861 and 1871) m Rebecca Smock (Smoke).

Anna (1809-1886) m 1st Jesse Thomas (d by 1834); 2nd Nathan Johnson.

Sarah (1811-fl. 1847) m 1st Benjamin Owens; 2nd John McNutt, 1837; 3rd John Fulmer.

Henry Miley (c1812-after 1861) m (Mary Pratton of Mersea, Cosfield Twp. 1841)?

Peter (1813-1882) Wainfleet Twp, m (Mariah?) Catherine Evans (1821-1889).

William Bradley (1815?-1873) Thorold, m Abbie McPherson, 1841?

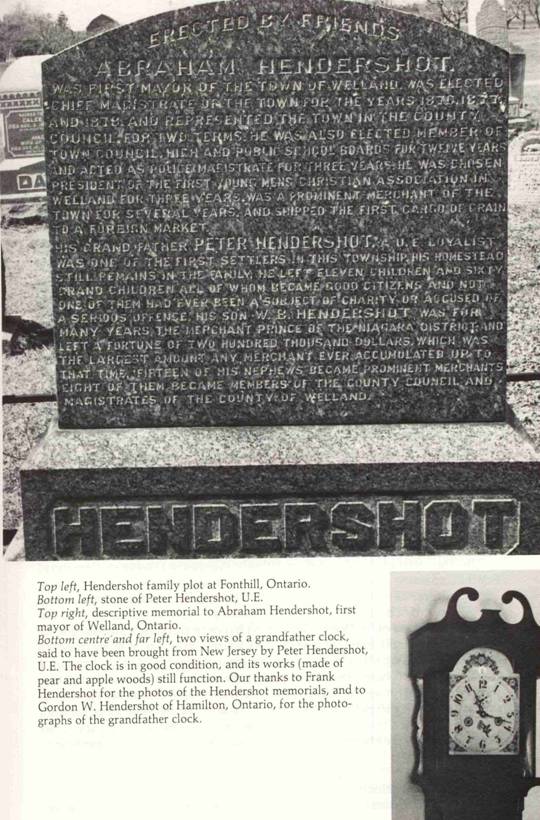

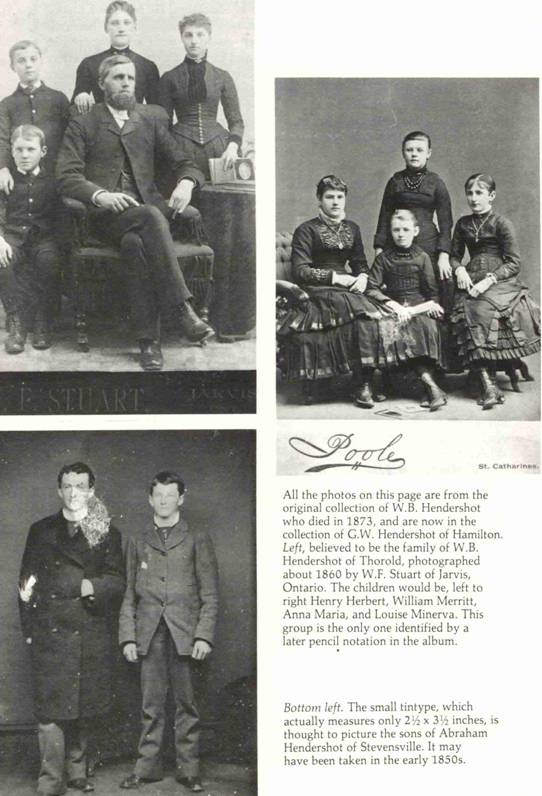

Note: The Top left, the Bottom left and one of the

clock pictures are found on page 21.

The family tended to lose contact with its members who moved far afield, such as Henry. Thus, in the present century it was known of them only that, say, two Johnsons moved to Montana, and that one of William's grandchildren moved to Utah. So statistics are incomplete. (Peter and Anna had at least 223 great-grandchildren from among 56 adult grandchildren—not including families of perhaps eight or ten whose whereabouts were unknown.)

The estate of Peter and Anna was not large consisting of 200 acres of their original Crown grant, which was sold in two parts, and 200 acres of more-promising land purchased in the same township. It is said that Peter supplied large quantities of beef cattle to the British Army and served as a teamster during the 1812 War. He was not a healthy man in his later years, and he died prematurely in 1819, aged 44. Few items were specified in his will by name: a bed, a bedstead, one cow, one sheep, and a spinning wheel—all to go to his wife. The rest of his property and the land were to be held by her for her life. However, according to his wishes that the land eventually be shared equally by the children, she soon began to give them their "undivided elevenths". Between 1841 and 1855 their youngest son William bought in eight of the eleven shares, and a son-in-law Henry Johnson purchased the other two.34b

The hurricane of 1792 affected some of the Pelham farms, among them that of Michael and Sarah (Hendershot) Henn/Hand.35 Michael was known as "Honest, Sober, Industrious, and inoffensive". Sarah, whether deliberately dishonest or merely confused, was at one time in danger of prosecution by the Crown for "having sworn to a falsehood" in claiming lands. Their three daughters married Pelham men in the first years of the 19th century. Ann married Henry Thomas and Sarah married John Overholt. Elizabeth married John Disher.

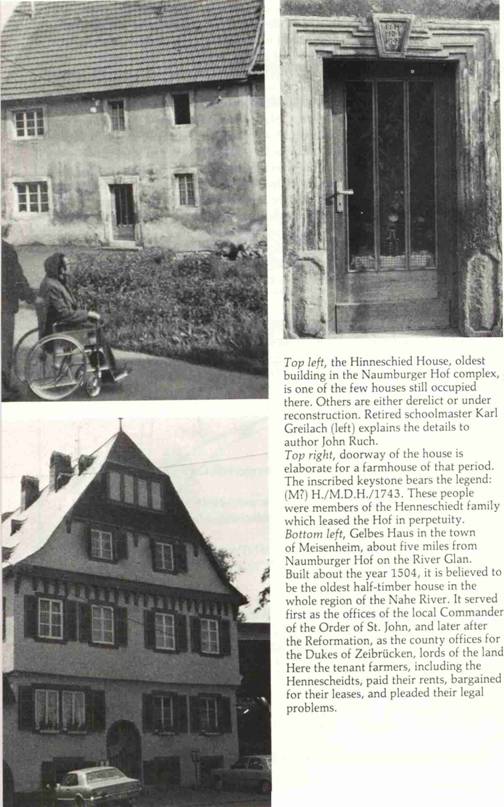

The Hendershot family plot in Hillside (formerly Dawdy's) Cemetery, Fonthill, contains few stones beside that of Peter and Anna. Nevertheless, a large gray granite memorial (erected c1900) to three generations of the family testifies to their changing fortunes. The principal accomplishments of three men are inscribed on it. Peter (1775?-1819) left eleven children and sixty grandchildren of upright and unblemished character. His son William Bradley (1815?-1873) among other things left the largest fortune yet accumulated by a merchant in the Niagara Peninsula. Peter's grandson, Abraham, son of Abraham, was the chief magistrate and first town mayor of Welland. It was important for the family to publicize these facts, for another Hendershot in western Ontario was then notorious. He had been brought to justice by the Great Detective (Inspector Murray) and was hanged for the murder of a nephew in 1895.36

The merchant prince

The most ambitious, gifted and successful of Peter's seven sons was the seventh William Bradley. While his reputation was still bright in the memory of local people, the Welland County historian wrote of him:

Mr. Hendrshot was one of the earliest merchants of Thorold having begun business there in a small grocery store, when the village was very small. As Thorold grew, his business expanded to very large dimensions, embracing not only one of the most extensive general stores in the Niagara District, but also large milling interests. At the time of his death in 1873, he had amassed a large fortune, after having been identified with the rise and progress of Thorold for nearly half a century.37

His keen business sense was allied to a strong feeling of public responsibility. In elected office he served two terms in the old Niagara District Council 1848-49, and was at first also a Thorold Township Councillor. In the decade 1851-61 he served five terms as reeve of the newly incorporated town of Thorold.38 He is said to have been a handsome and impressive two-hundred pounder. His 2nd great-grandfather Michael had established the family involvement in American church affairs; his grandfather Peter had begun the family tradition of military service in wartime. It was William himself who set the pattern for commercial and political activity, and achieved a standard which none of his relatives has attained since.

While William was in his teens the Pelham neighborhood was bustling with preparations for, and then the building of, the first Welland Canal. From the mid-1820s on through mid-century it was an exciting period for young and adventurous men. Construction of the Canal, in two successive projects, brought in masses of people not only as workers, but also craftsmen, merchants, and officials.

Local commerce increased enormously both then, and again later when the Canal was finished. Shipping and local industry throve. "Boom" settlements blossomed along the waterway: Allanburg, Merriton, Thorold, Welland, Wellandport. Port Robinson came to rival Chippawa as the important centre of communications for the Niagara area. Numerous firms such as the "Hendershot Brothers" located along the Chippawa Creek (Welland River) which was the original southern outlet of the Canal system. Many of these business involved wood industries and ship building.39

William B. Hendershot acquired a great deal of land and many businesses. No complete and detailed list of either of these possessions is known, but such would be very long. His will shows that he had land in nine townships of five counties, and in ten towns and villages. Most of this (in Haldimand, Lincoln and Welland counties, not to mention another two properties in Chicago, Ill. valued at $150,000), was to be sold by his executor to provide a regular income in interest for his children, with the principal eventually destined for his grandchildren. In addition to the money, he left each child several farm lots or parts of lots. None of his business interests was mentioned in the will. However, the "Smith Farm", Niagara Township, which he left to his son William Merritt Hendershot, must have contained the well known Queenston Quarry. High quality limestone from it was used in the mid-l9th century for Brock's Monument, for the Welland Canal, and for two Niagara River bridges. The son sold the Quarry in 1878.40 His father had also a sawmill and large interests in the Keefer flour mills at Thorold—then the largest in Canada, operating around the clock.

William Bradley's patronage

Up to the early 19th century the Hendershots had been mostly farmers. There are records of some coopers, weavers and tavern keepers—and in Germany a few tailors. Now in the Fonthill inscription we find stated:

"Fifteen of his (William B's) nephews became prominent merchants, eight of them became members of the county council, and magistrates of the County of Welland."

This is a startling contrast. To explain it in vague historical generalizations—the expansion of education, industry, and the rise of the middle class—is unsatisfactory for the genealogist concerned with individuals. An earlier family historian discovered the key to this sudden flourishing of the Hendershots in the combined generosity and business genius of William Bradley.

"In his kindness and heart he set nephews in business and opened for them a prosperous future."41

Thus numerous members of the family are to be found listed as "merchants" in the 19th and 20th century directories.

A good example of the effect of William's assistance to his relatives is the activity of his brother Abraham and his family. After having been a tavern keeper near Wellandport (on what is now called "Hendershot Road"), Abraham moved his family to Stevensville in Bertie Township about 1848. Under his direction his sons learned the business of general merchandising in a store which they built up to become one of the largest in Welland County. Peter (1830?-1917) continued here for many years after his father's death, which must have been hastened by the shock of two disastrous fires in early 1860. Peter, evidently in association with William B., had commercial links with George Stephen's business in Montreal. Purchasing trips were made to this city semi-annually, and Stephen (later Lord Mountstephen, President of the Bank of Montreal and the C.P.R.) expressed a high regard for Peter's integrity.

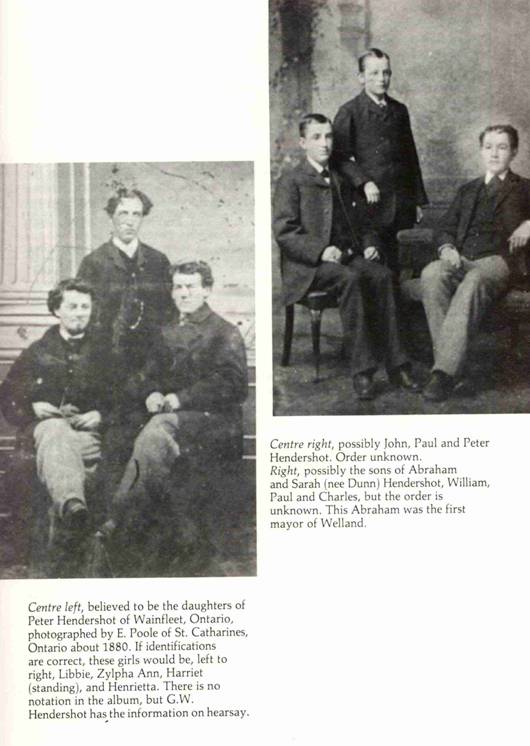

About 1860, two other sons, Abraham (1835-1920) and Paul Horton (1837-1923), set up in business in Fort Erie as "Hendershot Brothers", but did not stay long. They moved to Welland in late 1861, and Paul opened a branch in Dunnville in the late 1860s as "P.H. Hendershot". Abraham became heavily involved in local politics and public affairs such as the school board. As well as being first town mayor, he was chief magistrate 1876-78. It looks as if Paul returned to "mind the shop", but both moved to Dunnville in 1890. Paul retired some time afterward to a prosperous fruit farm near Stevensville where he grew large quantities of grapes, etc.42

All four of Abraham Sr.'s sons were prominent in the county. The second of them, John (1833-1914), was trained as a land conveyancer by Dexter D'Evrardo, later county registrar and a leading man of affairs. John also attended an American college and received a degree in education. He became a justice of the peace, postmaster, county councillor, reeve and schoolboard chairman of Stevensville. Abraham Jr. had also been involved with schoolboards in Welland. All four brothers were long-lived and thus had a more durable effect upon their associates than some of their shorter-lived relatives. John's literary interests were reflected in the next generation by the establishment of a printing works, which continued in family possession until fairly recent years. Involvement in this craft led other of Abraham Sr.'s descendants and relatives to establish firms that produced the raw materials for the printer—paper products, and inks. Some of these firms still exist, e.g. in Hamilton, and Montreal.43

The patronage of William B. was of unknown extent. We are aware that he bought patrimonial land from his brothers and sisters. On occasion he assisted them by taking mortgages on their other land: his brother Peter accumulated 125 acres in Wainfleet in 1848-53, 46 of which he mortgaged five years later to William B.44 Although the latter's influence lingered, all such dealing of course stopped with his death.

The children of Peter (1813-82), all born during the 1840s and 50s, mostly remained in the Wainfleet area, where there is now a Hendershot Road. They rejoiced in some resounding given names: William Henry, Sarah Elizabeth, Anna (Jane?), Peter Hamilton, Henrietta, Lafayette and Harriet. William Henry's only surviving son was named Peter Harcourt (1881-1966) after the highly respected local M.L.A. and Minister of Education, the Hon. Richard Harcourt. In turn, his son Frank Harcourt Hendershot carries in his middle name the memory of the man with "the golden voice". Peter Harcourt was for some years in the 1920s owner of the Niagara Ice Company in Niagara Falls, but later farmed in Willoughby Township. His second son William Peter operated Hendershot Hardware in Chippawa after serving in the army during World War II.45

The families of Peter Jr.'s descendants are widespread, although many have remained in Lincoln and Welland counties. It is in the area between Hamiliton and London that there is much confusion in the lines. Gordon Wesley Hendershot, veteran of World War I, and his Hamiliton family are descended from Abraham Sr. However, in Wentworth County and farther west we begin to encounter the descendants of Christopher.

The line of Christopher the Cooper

This family by itself deserves a great deal of research. When it is borne in mind that he is said to have had twenty-three children, seventeen of whom came with him to Canada in 1805, it is reasonable to assume that the number of his descendants is immense. Christopher (also called Christian; 1734?-1812) was a cooper who resided near Wise's Mill in German Valley, N.J. Twice he fell afoul of creditors, in 1766 and again in 1799. On the second occasion he was jailed ten months before any charge was laid against him. All his goods were seized, as was his family's clothing—save for what they were wearing.46 They migrated to Ancaster in 1805, probably with the large group of people from New Jersey who soon filled the area northwest of Hamilton, and built Jerseyville. Christopher and his second wife Christina survived the journey seven years. They are commemorated by the oldest gravestone in Spring Creek Cemetery, Peel Township near Mississauga.

Two of their children deserve special mention for a particular reason. While Peter Jr.'s (1775?-1819) children were too young to fight in the 1812 War, Christopher's boys John and Daniel both served in the Lincoln militia, 5th Company. John was the first casualty of the Queenston campaign, being killed while on sentry duty by an enemy sniper's bullet.47 He left a wife who died herself shortly afterward, and three children: Christopher, Margaret (m Cornelius Degraw, Mosa Twp.), and Madeline. The orphans appear to have been brought up by the family of Christian Almas. They later moved west, and young Christopher was captured during the Rebellion of 1837-38 as a rebel. Pardoned, he settled down to farming in Mosa Township, Middlesex County. He died aged about 52 years c1860, and his widow Elizabeth kept an inn to support her five youngsters Margaret, Hannah, John, James and another boy.48

Many of

Christopher Sr.'s descendants must be in southern Ontario. In 19th

century directories one finds them following various occupations: merchants,

pump-makers, wagon-makers, businessmen, postmen, etc. Late in the century many

Hendershots migrated west into the U.S.49 These

extensive families must await another genealogist.

This article is intended to inform the genealogist about the background of the Palatine emigration, and show the sort of documentation that can be found in archives if one is diligent and lucky. Some may not regard the Hendershot family as typical Palatines, yet they shared the sufferings of their contemporaries and followed the long path so many of them were to cover from the Rhine to the Thames, the Hudson, the Raritan, and finally the Niagara. Many members of these families will resemble what we regard as the ‘typical’ Hendershot: long-headed with dark hair and prominent nose, and a sturdy body. And who can not recognize in the person of some of his own relatives a reflection of the irascible old Hofmann Wilhelm whose farm "would have been much better arranged if he didn't go fishing so often" as the duke's Rent Collector complained? How much more information on the Palatines lies undiscovered in the vaults of various overseas archives—details of importance, of interest, or amusement to the searcher? This the individual has to find out for himself. It is a tedious, but often rewarding quest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It would require another article to list all the kind people who helped in this research and to show the importance of their contributions. I want to thank the Montreal staff of the Consulate General, Federal Republic of Germany, and of the Goethe Institute who were most co-operative. In Germany, those who discovered the essential clues which unlocked various mysteries were:. Dr. Else Emrich of Munich; Rev. A.H. Kuby of Enkenbach Pf.; Herr Oskar Poller of Ludwigshafen a.R.; and Herren Werner Beitsch and Norbert Heine both of Speyer. In North America the expertise of Henry Z. Jones of San Diego, California, the late Norman C. Wittwer of Oldwick, N.J., and John Mezaks of Toronto was invaluable. On the other hand, a number of correspondents provided masses of pertinent family information, notably William E. Hendershott of La Jolla, California, Alfred E. Hendershot of Mountain Home, Arkansas, Mrs. Roy Summers of Fonthill, Ontario, and Mrs. Carl Bernatovech of Levittown, Pennsylvania. My close relatives have been particularly helpful, but to mention only those who lent me photographs, I must thank Gordon W. Hendershot of Hamilton, Ontario, and Frank and Gary Hendershot, as well as my mother Winnifred (Hendershot) Ruch, all of Niagara Falls. My wife Elizabeth photographed the Naumburger Hof and decyphered the handwriting of many German documents. Others receive credit in the following notes for particular reasons.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Historical and geographical works will be mentioned first, followed by references to some genealogical material. The standard study of the Palatines for over a generation now has been W.A. Knittle, Early Eighteenth Century Palatine Emigration, 1937, reprint Baltimore 1965. A much older history of those who settled south and west of New York City is T.F. Chambers, Early Germans of New Jersey, 1895, reprint Baltimore 1969. Knittle has an extensive bibliography of earlier literature, and Chambers has many early genealogies. A recent and well researched article on another Canadian Palatine family is Marguerite R. Dow, "The Markells and Merkleys in Upper Canada", Canadian Genealogist. Vol.2, No.2, pp. 87-105. For German histories of the Palatinate see note 3 below.

Researching in Germany by correspondence can be made a good deal easier by using the recently published Lary D. Jensen, A Genealogical Handbook of German Research, Pleasant Grove, Utah, 1978. Guide books in either English or German have little to say about the majority of small towns and villages from which Palatines came, especially the poorer and less picturesque settlements off the tourist-beaten track. A German paperback which covers the Palatinate in some detail is Pfalz, Saarland nod Rheinhessen, in the Grieben "Deutschland" series no.138, rev. ed. 1975. Hofs such as Naumburger and Bremricher usually are shown only on the smaller scale maps, such as 2" to a mile. Useful for touring are two maps readily available in German bookshops: the Shell sheet no.15 (1:200,000 or about 1" to 3 miles, pub. Mair), and the Ravenstein sheet no.202 "Mittelrhein" (1:250,000). The Grosse Shell handbook covers the whole of Germany.

The only book devoted to the Hendershot family is a collection of numerous family group lists preceded by a short introduction, Alfred F. Hendershot, Genealogy of the Hendershot Family in America 1710-1960, privately printed in Akron, Ohio, 1961. He based his historical account of the family's German origin upon the writings of Cleveland B. Hendershot. Two manuscripts of the latter's composition are in the Newberry Library, Chicago. The smaller and shorter of these mostly repeats material from the larger manuscript. Unfortunately, Cleveland was an incurable romantic and exaggerated the nobility of his ancestry and the importance of his relatives. So his work must be used with a great deal of caution, and it has in the past misled a great many genealogical searchers. These included Chauncey B. Reece of Fenwick, Ontario, who about 1936 published a leaflet genealogy of the Canadian Hendershots The Hayder Family of Bavaria . . . Hendershot Family of Canada. A number of such productions have been made by various branches of the family, marred by the mythical history, but otherwise quite valuable for the information given about immediate relatives of the respective authors. Cleveland's father had been actually the legendary "Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock" of Civil War fame. A rare magazine commemorated his exploits, with illustrations, H.E. Gerry, Camp Fire Entertainer and the True History of Robert Henry Hendershot, the Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock, Chicago (Hack & Anderson) 1899.

From the dozens of variants of the surname I have used three as standard forms: Hinneschied, Henneschiedt, and Hendershot. This first follows F. Arnold's usage for the German ancestors in “Naumburger Hof”, Nordpfälzer Geschichtsverein, Rockenhausen, nos. 7 and 8, July-Aug., 1930, pp. 49-52 and 57-62. Henneschiedt is the form used by Knittle for the emigrant Michael as found in documents of Colonial New York. Some families, especially in the U.S. use the spelling Hendershott, although a single 't' ending is more common.

NOTES

1. Knittle, chap. 1.

2. Dow, pp. 87-89.

3. The old standard histories of the Palatinate, both in German, have been reprinted by Verlag Johan Richter, 678 Pirmasens, West Germany. Michael Frey, Geographisch-historisch-statistiche Beschreibung des königlichen bayerischen Rheinkreises, 1836-37 (reprint 1975, 4 vols. in 3) is a well-organized, more analytic treatment of the subject by a Catholic priest. Ludwig Häusser, son of a Protestant pastor, wrote an information-packed narrative history in his Geschichte der Rheinischen Pfalz nach ihren politischen kirchlichen und literarischen Verhältnissen, 2nd ed., 1859 (reprint 1970, in 3 vols.).

4. There are numerous histories of the Thirty Years War, e.g. by G. Pages, J.V. Polisensky, S. Steinberg, and C.V. Wedgewood.

5. Karl Ludwig's mother, called the "Winter Queen" because of her husband's brief reign, was a daughter of England's James I. His brother was the dashing, legendary Prince Rupert of the Rhine, who took part in the English Civil War.

6. Häusser cites a figure of 98% loss of population, vol.III, p. 583. A figure of about 60% is given by C. Veronica Wedgewood, The Thirty Years War, London, 1938, in an interesting account of the exaggerated claims originally made by survivors pp. 510-516.

7. Häusser, vol. III, chap. VI, on Karl Ludwig; vol. IV, chaps. I-II on his successors.

8. The Naumburger Hof documents are in Bestand B 2 (Zweibrücken Akten), nos. 903/2 and 904, those for Bremricher Hof no. 907/12 all in the Landesarchiv, Speyer.

9. Hof means “court”, and carries with it most of the same meanings as the English word. A courtier or nobleman is a Höfling. Estates similar to the Hof would be called a Bauernhof if owned by a farmer, a Landgut or Gut if owned by a non-noble Patrician.

10. The folio notebook containing the map is in Bestand B 2, no.903/2, p.460, Speyer. For a century and a half until 1694, Meisenheim was a principal seat of the counts of Veldenz, especially after the French destroyed their great castle Veldenz near Lauterecken. Meisenheim is reputed to be the only town in the Palatinate which escaped destruction during the Thirty Years War. Of the town palace (Schloss) only two wings now stand: the royal chapel, a jewel of late Gothic architecture now used as parish church, and a residential building which serves as a Lutheran hostel.

11. Arnold, pp. 49-52.

12. ibid.

13. Peasants would now agree to only a few of the old feudal obligations, such as carting the lord's supplies once or twice a year. Some of the old compulsory work has been commuted to payment of a tax, ibid.

14. H.Z. Jones sent me a copy of Anna's 1709 petition, B 2, no. 904, f. 85, Speyer.

15. It is often difficult to distinguish which religion people belonged to, for it was necessary that Protestants be registered in Catholic books which were becoming the only legally recognized religious records. So Protestants were frequently double-registered, being baptized, etc., twice in different ceremonies. An ancestor who was twice registered for the same type of rite was certainly a Protestant. This is the case with Christoph's son Johann Ludwig. whose marriage can be found in both the Protestant Meisenheim church records, and in Catholic Feilbingert church register in 1744. These were discovered, respectively, by G.F. Anthes, and 0. Poller.

16. The 3,000 florins (= 2,000 Reichstaler) could probably have bought about 200 good milch cows, or 160 hefty oxen.

17. For the explanation of the mistaken claim to nobility see John E. Ruch, "Doubtful, Erroneous and Spurious Claims," heraldry in Canada, vol. XIII, no. 3 (Sept.1979), Ottawa. pp. 27-34.

18. Many details on Joh. Ludwig's family were supplied by G.F. Anthes.

19. Opinions from Dr. H.W. Friedrichs, Frankfurt a. M. and Prof. R.M. Kully, University of Montreal.

20. W. E. Hendershott found nearly a dozen families in the 1880 Census Soundex records, and worked backward through Censes to 1850, locating families in Missouri, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, and Pennsylvania along the way. Family heads with approximate dates of arrival in the U.S.: Martin Hintershield, Ohio 1858; John Hintershied, Ohio 1864; Peter Hinterschitt, Ohio 1862; Crishoph Henershit, Penn. 1871; Jacob Hinderschid, Missouri 1869; Nicholas Henterscheid, New York 1879; John Henderschaet, Minn. 1872; Henry Henderscheidt, Minn. 1873; Jacob Henderschaet, Minn. 1880.

21. Alex. F. Schwartz kindly procured copies of many documents tracing Heinz's origin to Jakob Hinneschiedt, a tailor of Wöllstein in 1772. This indicates that he was almost certainly a descendant of the Bremricher Hof family not far away. Heinz's statement about name change was made in a letter to his old school the Ratsgymnasium, Hannover, written 12 December 1956.

22. N.C. Wittwer pointed out that Michael received a higher and longer allowance than the others in his group, but cannot account for this difference. Records of government subsistence are C.O. 5/1231 in the Public Record Office, London, Eng. See Knittle, p. 282.

23. The passage from Weygand's Diary is quoted in T.F. Chambers, pp. 70-71. Numerous references to his own work with the local congregations are contained in Henry Melchior Mühlenberg’s Journals, 3 vols, 1942-58 Philadelphia. e.g. visiting the sick in Racheway (Rockaway = Potterstown) late July 1748, vol. I, p. 200. The trouble between Michael and Falckner is dealt with in the Wilhelm C. Berkenmeyer, The Albany Protocol 1731-1750, ed. J.P. Dern, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1971, pp. 10, 18-19. A letter written for Michael to church authorities is in Simon Hart and H.J. Kreider, Protocol of the Lutheran Church in New York City 1702-1750. New York, 1958. Also numerous refs. in their Lutheran Church in New York and New Jersey 1722-1760, Ann Arbor, Mich., 1962, see index under "Hunerschutt".

24. The original lease of Hohenhaus property for 110 years is in possession of the present owner. For a map of the original lots see Chambers, p. facing 194, also pp. 195-196. Wittwer explained

the original form of the church to us, and provided the reference to the approval of a tavern license for one Michael Hendershot dated 1 May 1761.

25. Mühlenberg. Journals, vol. 1, p. 397.

26. Supreme Court Docet 1742-1745, 9 November 1745. This gives the surname as "Hennezeit". “Henne" is either Johann Hinrich, illegitimate son of Michael Sr.'s daughter (Elizabeth?) bapt. 2 August 1719, or John the youngest son of Michael Sr. (The illegitimate birth was registered by Rev. Justus Falckner, see records of Lutheran Church of New York City, pub. in New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, also on LDS microfilm reel no. 4005.) In 1743 the first survey of the boundary between the East and West Jersey Proprietors' lands showed that many properties already leased out by one or other of them were actually in the other's jurisdiction. This resulted in a number of legal actions being taken to recover or exchange land.

27. Writs of Hunterdon County Court, Hall of Records, Flemington, N.J. Surname spelled variously, Endershett, Hendershatt, etc.

28. K. Stryker-Rodda, "The Janeway Account Books", Genealogical Magazine of New Jersey, vols. 33-35 (1948-1960). Names of John Peter Nitzer's customers are in Chambers, pp. 636-7.

29. Identified by Philip Nordell, information from N.C. Wittwer.

30. Muster rolls of the Volunteers are in the Military 'C' ser., vols. 1855, and 1856, National Archives of Canada, Ottawa (microfilm reels C.3874 and 4216). Transcripts are in the State Archives, Trenton, N.J. At least 36 veterans of the regiment settled in the Home (Niagara) District according to the Old United Empire Loyalists List, Toronto, 1885. Boyle, Hazen, Hendershot, Henn, Slighter, Thomas, Whitsell, and two Wilsons called it "Barton's" corps, regiment, or volunteers. Peter Hendershute was imprisoned in Essex County, according to notes supplied to me by Thomas B. Wilson from Minutes of the Committee of Safety, Jersey City, 1872.

31. On Alsatians see John E. Ruch, "The German-French of Willoughby Township," Families, Toronto, vol. 17, no. 1 (1978), pp. 25-38.

32. Baptisms of Priscilla and John are on LDS microfiche (New Jersey, p.1,055), note from W.E. Hendershott. Their mother was baptized as an adult by Mühlenberg, see his Journals, vol. I, for 17 June 1758. The Phillips family was numerous in Amwell Township.

33. On intermarriages of the first Canadian-born generation see Elinor Mawson, Uncle Abraham, St. Catharines, Ont., 1979. For Christina and William see her land petitions in the PAC ref. H 9/82 and H 11/18 (in 1810 and 1817 resp.). Her second husband is mentioned by Maryly B. Penrose, "The Ontario Branch of the Bauman/Bowman Family," Families, vol. 16, no. 2 (1977) p. 62.

34a. The principal sources for Peter are in land papers: land Petition, NAC; Pelham Township papers (microfilm in Ontario Archives); his will also exists, being filed in Lincoln County Probate Court. W.D. Reid, Loyalists in Ontario, Lambertville, N.J., 1973, p.146 lists the family incorrectly, confusing Peter the soldier (whose daughter was Sarah Henn) with Peter Jr., who had the eleven other children shown, including the third Peter. Information on the Johnson children was supplied by Roy Johnson, Ridgeville, Ont.; on Sarah Jr.'s children by Mrs, Jean Wagner, Orchard Lake, Mich.; on William B.'s children by the late A.R. Petrie, St. Catharines, Ont. Data on the rest comes mainly from Census 1851 to 1871. The 1795 certificate for Peter's petition was brought to my attention by John Mezaks, Ontario Archives.